Starting from scratch

Thoughts on a recent visit to Nusantara, Indonesia's new capital city

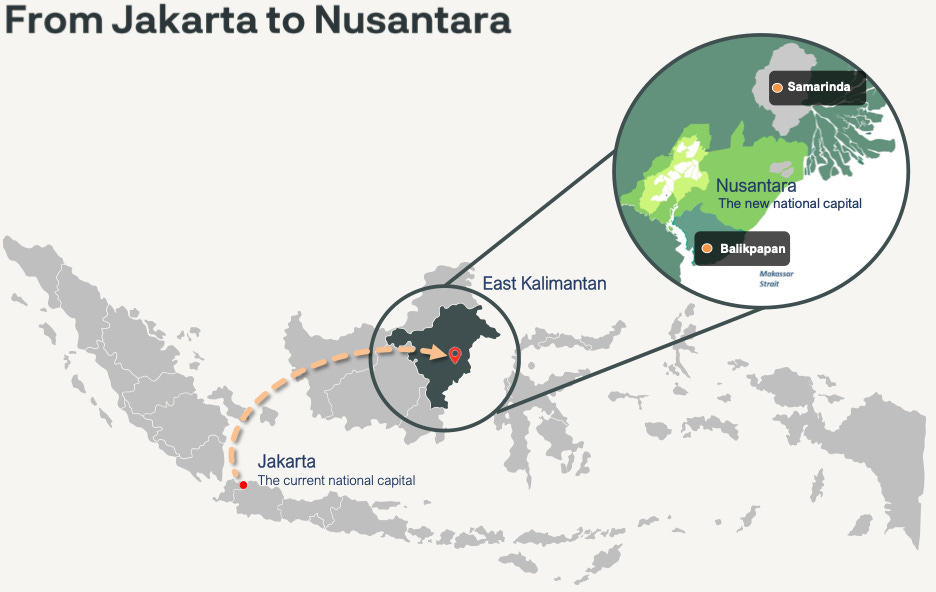

Building, or at least relocating, a capital city is in some ways a rite of passage for rising regional powers. Indonesia, home to over 270 million people, is one such rising power. Deep in the jungles of Borneo today is a muddy clearing that Indonesia hopes will become the center of its new capital city, Nusantara, in just 15 months.

[The New York Times recently published a comprehensive feature of Nusantara; I recommend it as background reading for anyone unfamiliar with the project.]

In March 2023 I chanced upon an opportunity to visit Nusantara during a business trip to Kalimantan. After a bumpy 2-hour ride through the literal rainforest, I arrived at a quiet construction site. Idle cranes. Empty trucks parked on the side of muddy roads. Construction workers and security guards napped under the gazebos where politicians posed for photo ops in months prior.

Nusantara is not a China-style mobilization of national resources (yet?), but there nevertheless were signs of progress: the trees had been cut down, the land flattened, and there were dozens of prefabricated (if not occupied) dormitories for workers.

The seemingly slow process only reinforces existing skepticism surrounding the project. Funding is a big issue. The government has said it will only fund 20% of the estimated $32 billion initial cost, and that it will find (yet-unnamed) outside investors to pay for the rest. Popular support is also mixed, with some 60% of Jakarta residents said they were opposed to the project.1 Only one of the half-dozen candidates rumored to be running to succeed Jokowi have outright committed to continuing the project.

Cities take time to build

Let’s first cut Indonesia some slack. Seven years passed between when the first cornerstone was laid in 1793 and when the U.S. Congress officially moved from Philadelphia into the (still-under-construction) Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. Canberra, Australia took 16 years to reach that same milestone; Abuja, Nigeria, took 20 years. Brasilia was the fastest to be built among capitals relocated to the middle of nowhere.

Read past the headlines and you will quickly discover that Indonesia has set far more humble targets for itself: not a bustling capital city but enough to hold a flag raising ceremony on August 17, 2024, two Indonesian Independence Days from now. It will be years, if not a decade, before the city begins to fill up (nor is it guaranteed that it ever will! See: Naypyidaw).

Building 21st century values

As the first new capital city built in the 21st century, the plans for Nusantara incorporate almost every architecture and urban planning fad of our time: green roofs and solar panels; “smart” lamp posts and traffic lights; self-driving electric cars next to bike lanes; all surrounded by trees as far as the eye can see. The centerpiece will be a neo-futuristic, green glass-and-steel Garuda, the winged Hindu demigod that is a symbol of Indonesia.

The designs of new capitals reflect the aspirations of the country they are built for: Washington, D.C.’s classical revival statehouses harken to the ancient democracies of Greece; Brasilia, New Delhi, and Islamabad—postwar international modernism; Astana—futurist bureaucracy? Nusantara reflects how countries are developing today: modernizing with token elements of tradition and nature.

Green capital on coal island

Outside of Indonesia, the island of Borneo is known for its ancient rainforests home to orangutans, cloud leopards, and countless other unique species. Within Indonesia, Borneo is known as the island of coal. Locals joke that you can find coal just by digging in your backyard. One-third of the GDP of East Kalimantan (one of the Indonesian provinces on the island of Borneo) is coal and lignite mining.2

Nearby Balikpapan was founded as a company town by the Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij, a former subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell and a predecessor to Pertamina, Indonesia’s state-owned oil company. At over $11,000, the Balikpapan-Samarinda metropolitan region actually has a higher GDP per capita than even Jakarta. You see hints of the wealth walking down the streets: locals dressed head-to-toe in international brands, holding the latest iPhones, driving (or being chauffeured) around in Range Rovers and Lexus’.

This is a problem for the new capital. For now there is a shortage of local labor—why toil away in the jungle two hours away when you can earn three times as much at the Pertamina refinery in the center of town? And despite Kalimantan’s resource wealth, there is still little value-added processing done locally: everything from precast concrete blocks to the temporary worker dorms are shipped in from Surabaya on Java.

The lack of advanced industry is nothing new for Indonesia’s outer islands of course; this has been their economy since the days of the nutmeg trade. And one of the goals of the new capital is to change that: to incentivize investment and industrialization outside of Java.

https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2022-54-analyzing-public-opinion-on-moving-indonesias-capital-demographic-and-attitudinal-trends-by-burhanuddin-muhtadi/

https://iesr.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Coal-Transition-in-Indonesia-Jakarta-April-2019-2.pdf